Category — Why and how we age

In it for the L-o-n-g Haul

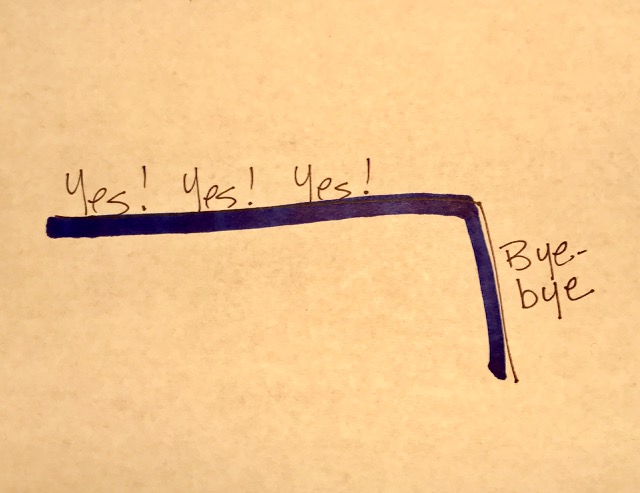

Rectangularization of Morbidity. It trips lightly off the tongue, does it not?

It does not.

It is the anthem of my life. My motto. My hope for the future. The goal I work toward every day. The bumpersticker I would put on my car if I had a really really long bumper.

What is it?

Simply put: Do all you can to create, nourish and maintain high-level wellness and maximum vitality. Sustain that state for as long as possible. Then die. Or, as I’ve expressed it to audiences when I talk about this:

Healthy, healthy, healthy, healthy, dead.

This is the opposite of how most of us age. We are, most of us, living much longer lives these days. The dramatic increase in life expectancy is heralded as one of 20th century society’s greatest achievements. Life expectancy for someone born in 1900 was 50. Today, in the US, it is 79. (In Japan, it is 84.)

But our healthspan – our years of healthy living — has not increased. That means we are living out the last 5, 10, 20 or even more years of our lives with often debilitating chronic illness(es). The average elderly person in the US is taking five different prescription medications. (For those in nursing homes, the number is seven.)

The third third of our lives – a gift! – is spent without the strength, vigor and energy to live fully, to participate with physical, emotional and creative vigor in the lives of our families, our communities, our nation. There is so very much to do, these days more than ever. We, all of us, young, old and in between need to meet these challenges with enterprise and élan, with zest and zeal, with sustained in-it-for-the-long-haul optimism. How to do that?

Rectangularization of Morbidity.

June 28, 2017 No Comments

Why do we age?

A simple question… without a simple answer. That’s because there is no one answer. Aging is a complex, convoluted still-not-well-understood series of interconnected processes. And the more we discover (we know a lot more about aging now than we have ever known), the more complicated it gets.

So where does that leave us — ”us” being those who want to continue to live vibrant, energetic, engaged, useful lives for a long, long time? We know that aging results in (and is the result of) the accumulation, over time, of detrimental changes at the molecular and cellular level that eventually affect tissues and organs. But the process (both “natural” and of our own making) is very very complicated. What seems to stand out from everything I’ve been reading, a kind of aging “refrain” if you will, is inflammation – the many and interconnected links researchers have been finding between aging and inflammation.

I don’t mean acute inflammation…the heat, swelling, redness that happens when you hurt yourself or get an infection. I mean invisible, systemic inflammation that affects body organs and physiological processes without us even realizing it. Until, that is, we DO realize it because something is going seriously haywire. As in cancer, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, etc. In fact, many diseases common to older people have clear inflammatory components. Researchers strongly suspect that inflammation both reflects the development and progression of disease and promotes disease evolution itself. Exactly how, and for which diseases, is the subject of intense study. For now, here are a few very specific and helpful things we know about inflammation and choices we make that can help with counterclockwise living:

>Smoking (and, to the same extent, exposure to second-hand smoke) stimulates inflammatory responses.

>Physical activity lowers levels of inflammatory markers.

>Diets low in fiber, high in processed grains, saturated fat and – particularly – red meat (aka the typical American diet) are strongly associated with inflammation.

>Conversely, diets rich in vegetables, fruits, nuts and fish are associated with low (or reversal of) inflammation.

>A pessimistic (or I-am-victim) attitude is associated with inflammation.

>The inability to creatively deal with life’s stressors is associated with inflammation.

Maybe some day there will be definitive answers to this huge, important “what causes aging?” question. But while we’re waiting, we can — and should – do whatever we can to control and mitigate our inflammation responses.

April 8, 2015 No Comments

Oh, Kylie…

Kylie Jenner Promotes Anti-Wrinkle Skincare Line: Is The 17-Year-Old Too Young? is the headline. Is there any possible response to this question that isn’t “yes”? Well, okay, in fairness, there are also these responses: Are you kidding me? WTF? Who cares? And, why, Lauren, do you even know this?

Kylie Jenner Promotes Anti-Wrinkle Skincare Line: Is The 17-Year-Old Too Young? is the headline. Is there any possible response to this question that isn’t “yes”? Well, okay, in fairness, there are also these responses: Are you kidding me? WTF? Who cares? And, why, Lauren, do you even know this?

Kylie Jenner, by the way, is the 17-year-old reality star and Instagram queen who is little sister to the infamous Kardashian women. And, just to get this out of the way, I don’t follow her on any of her multitudinous social media platforms. I receive daily Google Alerts for “anti-aging,” most of which alert me to crap like this.

Kylie is apparently “very concerned about the signs of aging” (shame on you for even thinking about clicking on that link!) and has been named the new brand ambassador for a British cosmetic company. Her favorite skin care product, should this for some reason interest you, is Viper Venom Wrinkle Fix Cream. I don’t know if real vipers are involved, but given what we know about the labeling of ingredients in non-regulated industries, I kinda doubt it.

Why am I even writing about this today? I’m writing about it because it allows me to pounce on this dangerous, ill-informed definition of “signs of aging.” No, in fact, 17 is NOT too young to care about “the signs of aging” – the important, life-changing signs that affect heart, lung, artery, muscle, bone and brain health. Notice I did not include wrinkles, which, as far as I know, never killed anyone or slowed anyone down or made anyone less creative, curious, resilient or engaged.

Kylie should care about building bone density while she can. She should care about establishing exercise, eating and sleeping habits that will set the stage for slow, healthy aging in the decades that follow. She should care about the quality of the air she breaths and the water she drinks. She should care about developing a variety of coping mechanisms that will help her handle life’s stresses and challenges. She should care about UV exposure.

I wish people – even 17-year-old people – if they are going to obsess about aging, obsess about actual, harmful, internal biological aging. Be a brand ambassador for that, Kylie.

March 18, 2015 No Comments

Biomarker #6: Strength

For years and years — okay decades — I was a cardio-only exerciser. I swam. I biked and hiked. I treadmilled and EFXed. I cross-country skiied. Now that I understand the importance of muscle building and maintenance to overall fitness, health and vitality, I train with weights three times a week. At home, I like the 7-minute workout (app is free), which I repeat three times. At the gym, I alternate between free weights and machines. I also take classes at Barre3, an studio routine that uses very light weights and very small movements and is probably the hardest (and most satisfying) exercise I do right now. All help build muscle, which is far more metabolically active than fat. That means muscle burns more calories, even when you’re not using it — so muscle-maintenance is weight maintenance. But, more important, building and maintaining muscle is a major anti-aging strategy.

For years and years — okay decades — I was a cardio-only exerciser. I swam. I biked and hiked. I treadmilled and EFXed. I cross-country skiied. Now that I understand the importance of muscle building and maintenance to overall fitness, health and vitality, I train with weights three times a week. At home, I like the 7-minute workout (app is free), which I repeat three times. At the gym, I alternate between free weights and machines. I also take classes at Barre3, an studio routine that uses very light weights and very small movements and is probably the hardest (and most satisfying) exercise I do right now. All help build muscle, which is far more metabolically active than fat. That means muscle burns more calories, even when you’re not using it — so muscle-maintenance is weight maintenance. But, more important, building and maintaining muscle is a major anti-aging strategy.

More muscle. Less fat. That’s the idea. I’ve written before about the fat-to-lean ratio as a biomarker of aging. Here I want to talk about strength (as a consequence of muscle) as a biomarker.

Older people are “weaker” than younger people because older people have less muscle mass, and the muscle they do have is less dense and works less efficiently. Between the ages of 30 and 70, the average person loses 20 percent of the “motor units” (the bundles of muscle fibers and the associated nerves that make up a muscle) in large and small muscle groups, and 30 percent of all muscle cells. And the cells that remain get smaller. And are marbled with fat. Less muscle equals less strength. Less strength leads to “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up” and other such horrors of old(er) age. Less muscle means less endurance. Less endurance leads to less activity which leads to decrease in muscle…and so it goes.

The beauty of this — I know this doesn’t sound beautiful, but hold on — is that the progression (or, really, regression) is linear and logical, and therefore both understandable and fixable. So we can reverse it. Much of the weakness of older people has less do to with the passage of time than it has to do with the passage of time spent on the couch. Lack of strength is not a “natural” consequence of aging. It is a natural consequence of not actively building and maintaining muscle. Emphasis on the actively. Want the energy, stamina, strength and endurance that will keep you healthy and vital? Build muscle. Want a youthful fat-to-lean ratio? Build muscle. When you build muscle you build endurance which helps you…you guess it, build muscle. And you know what? It’s even kind of fun.

July 10, 2014 2 Comments

Biomarker #5: Fitness

Suppose we could easily see how we are aging on the inside. I mean actually see, like look in the mirror and see the state of our heart, lungs, arteries, muscles, bones – instead of seeing how we are aging on the outside, those very visible but ultimately meaningless markers like wrinkles, sags and gray hair.

Suppose we could easily see how we are aging on the inside. I mean actually see, like look in the mirror and see the state of our heart, lungs, arteries, muscles, bones – instead of seeing how we are aging on the outside, those very visible but ultimately meaningless markers like wrinkles, sags and gray hair.

No one wants to look in the mirror and see an “old” person – I sure don’t. This not-wanting-to-see fuels a $10 billion a year (in the US) cosmetic procedure industry plus a billion or more dollar a year anti-aging cream/ serum/ miracle moisturizer market. If we could look in the mirror and see inside ourselves, see clogged arteries or fat-marbled muscles (sorry) as easily as we see crow’s feet or wattle-neck would we pay more attention to the real and important markers of aging? I say yes.

Well, we can look inside more easily than you might imagine – although not as easily as gazing at our faces in the mirror. I’ve been writing, off and on, about the biomarkers of aging like resting heart rate, blood pressure and BMR. These are easy to determine, and they say quite a bit about our age on the inside, where it counts.

And even better peek at our inside-the-body aging comes from measuring VO2max. VO2 max measures the body’s maximum capacity for transporting and using oxygen during exercise. The more oxygen you are able to use, the better shape your heart, lungs and arteries are in, and the more youthful and lively your mitochondria are (which also means the more youthful your metabolism is). In essence, the higher your VO2 max, the fitter you are, the younger you are. On the inside. Where it counts.

Norwegian researchers who tested almost 5,000 of their countrymen and women between the ages of 20 and 90, found that fitness (measured by VO2 max) was “even more important to cardiac health than previously thought.” And cardiac and cardiovascular health is central to maintaining an active, vital counterclockwise lifestyle.

You can go to a sports clinic or health resort or upscale gym and get a VO2 max test. It will cost you in the neighborhood of $100. It’s a strenuous test that takes place on a treadmill or a stationary bike and involves nose clips, breathing mask, head gear, lengths of tubing, monitors, computers and a significant amount of sweat. As readers of Counterclockwise know, I had my VO2max tested (four times) for free by volunteering to be guinea pig at a sports clinic. Believe me, they got their $100 worth.

If subjecting yourself to the actual test doesn’t appeal to you (or your pocketbook), but you are interested in getting a sense of what your VO2max might be – and I’m telling you that you should be — I found this website. You enter basic information, click and get your VO2max score that you can then read more about. I like this site because 1) It is operated by the Norwegian university scientists whose study I mentioned above 2) It is noncommercial 3) Your results are calculated using their large and credible database 4) The site told me I have the fitness level of a 25 year old.

April 30, 2014 2 Comments

Biomarker#4: Fat-to-lean

What’s the scariest number you can imagine? The cost of good health insurance? The number of messages in your inbox after a week’s vacation?

What’s the scariest number you can imagine? The cost of good health insurance? The number of messages in your inbox after a week’s vacation?

No. It’s your percentage body fat at mid-life.

Of all the biomarkers of age, of all the stats that determine how old you really are, biologically, percentage fat and its slender sibling, percentage lean, are among the most significant. The average American loses 6.6 pounds of lean body mass every decade from young adulthood into middle age. At age 45, the rate accelerates. The body of the average 25-year-old woman is 25 percent fat. The body of a (sedentary) 65-year-old woman is, gulp, 43 percent fat (men: 40 percent).

This increase in fat is accompanied by a decrease in muscle mass, which leads to a decrease in strength and general vitality. This condition even has a name – and it’s NOT “getting older.” It’s sarcopenia, Greek for reduction of flesh. It is a game-changer, or a paradigm shift, to consider that something we are accustomed to blaming on chronological age might be a “condition” caused not so much by the number of years we have lived but how we have lived those years.

The fat/ lean ratio is not just about appearance, although it goes without saying that, chunky-thighed, pudgy-cheeked babies notwithstanding, less fat and more muscle can make a body look decades younger than its calendar years. So appearance matters, yes. But there’s far more going on here. The high fat/ low lean thing – sarcopenia – causes, triggers or is closely linked to other markers of aging. Metabolism, for example. Young people, with lower percentages of fat have higher metabolisms. That’s because one pound of fat burns two calories a day, and one pound of muscle burns 35. We’re not slowing down because we’re older. We’re slowing down because we’re, well, fatter.

In addition to slowing down the metabolism – making it, need I add, easier to gain even more fat – high body fat is related to increased glucose intolerance which leads to insulin resistance on the path to type 2 diabetes. Not a road one wants to travel. High body fat ratio is also implicated in elevated bad cholesterol and “old” arteries (ones that do not dilate fully).

But wait! There is a cure for sarcopenia!

And no it is liposuction. No, it is not Human Growth Hormone or DHEA. And, sorry, the cure cannot be found in the supplement/ nutriceutical/ pharmaceutical/ anti-aging commercial marketplace, which is chockful of products that tout “extreme muscle builders” that “mobilize fat” to give “the best body ever.”

If you take moment to follow up those claims like I did, you’ll discover that the top-selling fat-busting/ muscle-building supplement, Hydroxycut, has encountered some major problems, like: jaundice, seizures, cardiovascular problems, liver damage and one documented death. The FDA ordered a recall back in 2009, but the product line is still available everywhere. Don’t buy it.

So what’s the cure? You know what I’m going to say…

Exercise. Movement. Physical activity.

The results are astonishing. And documented.

April 2, 2014 No Comments

Biomarker #3: BMR

And now…back to biomarkers, those statistical snapshots that can help us figure out how old we are biologically and then can track our counterclockwise movement as we live healthier, more active, more engaged lives. I’ve already written about resting heart rate and blood pressure as important biomarkers. To review: Low resting heart rate = good. Low blood pressure = good. “Good” means fit and biologically youthful. With Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), the opposite is true. A high BMR is associated with biological youthfulness.

And now…back to biomarkers, those statistical snapshots that can help us figure out how old we are biologically and then can track our counterclockwise movement as we live healthier, more active, more engaged lives. I’ve already written about resting heart rate and blood pressure as important biomarkers. To review: Low resting heart rate = good. Low blood pressure = good. “Good” means fit and biologically youthful. With Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), the opposite is true. A high BMR is associated with biological youthfulness.

So, what’s BMR (sometimes also referred to as Resting Metabolic Rate, which is not the same. but is enough the same for our purposes)? BMR is a measurement of the amount of energy we expend at rest. It’s the energy the body uses to maintain itself, the energy expended by heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, nervous system, all the internal organs that support life. If we lie in bed, absolutely still in twitchless slumber – or, less appealingly, if we found ourselves in a coma – we would still be expending energy. That’s our personal BMR. Although the mathematical calculations to get to BMR are mind boggling (at least my mind boggles), the measurement itself is easily understood. It is expressed in calories. Back to that in a second.

First, here’s something pretty interesting: About 70% of a human’s total energy expenditure is due to the basal life processes within the body’s organs. About 20% of our energy expenditure comes from physical activity and another 10% from thermogenesis, or digestion of food. Which kinda puts exercise in perspective, doesn’t it? And almost makes you want to do an over-eating, under-exercising experiment to see if you can make the math work in your favor. Spoiler alert: You can’t)

So why would a higher BMR be associated with biological youthfulness? It’s because BMR is strongly linked to muscle mass. The greater the muscle mass, the more felicitous the lean-to-fat ratio (as in more lean, less fat), the higher the BMR. Muscle is metabolically active. It uses more energy just to maintain itself than does fat. So an in-shape, leaner body burns more calories and registers a higher BMR. Men, by virtue of their generally bigger bodies and genetically determined greater muscle mass, have higher BMRs than women. Which is why your husband, most infuriatingly, can eat twice what you do and not gain a pound.

It is stated in the literature that “BMR decreases with age” and that, more specifically, our “metabolic rate goes down about 2 percent or more per decade after age 25.” Well, sort of. Yes, BMR decreases — but not because years pass. It’s because muscle mass decreases. Here’s what Tufts university researchers say: “Older people’s reduced muscle mass is almost totally responsible for declining BMR.” In other words: You can have a major effect on your BMR by increasing and maintaining muscle mass. Thus BMR is yet another biomarker over which we have considerable control.

So, how to determine BMR:

1. Easy (and not terribly accurate) Here is link to a BMR calculator. Here’s another one. The problem: They both use your chronological age, making assumptions about muscle mass that may not be true for you.

2. Expensive (and accurate) Find a sports or health clinic that uses indirect calorimetry to measure BMR. It involves breathing into a mask/ apparatus attached to a computer with sophisticated software that measures the oxygen/ carbon dioxide mix. You have to be capable to truly relaxing and zoning out with a mask over your face in a clinical setting. And willing to pay $150 or so.

3. Easy, inexpensive, accurate. This assumes you already own a heart monitor, the kind with the watch and chest belt. Make sure you’ve recently/ accurately input your weight and height (and gender, of course). Strap it on before going to bed and press the start button when you are comfortably situated and just about to fall asleep. The next morning, see how many calories you burned while asleep in how many hours, divide by the hours, then multiply by 24 for your personal BMR. Do this several nights and take the average as you may have a particularly restless night that would skew the results. Try it!

March 19, 2014 No Comments

BIOMARKER #2: Blood pressure

We’re talking BIOMARKERS again this week (and for the next few weeks). Biomarkers are, you might remember from last week’s post, statistical snapshots – based on solid research – that can help us determine how old our bodies are. Which is, birthdays not withstanding, how old we really are.

We’re talking BIOMARKERS again this week (and for the next few weeks). Biomarkers are, you might remember from last week’s post, statistical snapshots – based on solid research – that can help us determine how old our bodies are. Which is, birthdays not withstanding, how old we really are.

Last week I wrote about resting heart rate. This week’s biomarker is blood pressure.

First, a little primer: Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of arteries. Blood pressure measurements are given in two numbers. The first number (systolic blood pressure) is the pressure caused by your heart pushing out blood. The second number (diastolic blood pressure) is the pressure when your heart fills with blood. The safest range, often called “normal” blood pressure, is a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 and a diastolic blood pressure of less than 80. This is stated as 120/80. Elevated blood pressure increases the risk of heart attack and stroke and, if left untreated, can reduce life expectancy by 10 years or more.

An increase in blood pressure has always been taken as an inevitable consequence of aging. But what it is, is a consequence of a progressive lack of elasticity of the arteries along with a weakening of the heart muscle. So are those changes the natural, inevitable consequences of the passage of time?

Some artery “hardening,” and thus some elevation in blood pressure (the systolic number), may come with age as well as some (perhaps small) lack of efficiency in the heart muscle. But it is not so much the passage of time as the accumulated effects of unhealthy living that lead to high blood pressure. And, of course, it’s the usual suspects, the poor habits that have become increasingly ingrained in western culture. You know what they are, folks: smoking, consuming high (bad) fat food, eating foods high in sodium, weighing more than is healthy and not exercising.

Normal, or not-scarily-low blood pressure (achieved without medication) is a sign of a strong, efficient heart and healthy, elastic arteries. Normal or lower blood pressure, then, is a biomarker for youth. Maintaining a consistent “normal” reading for systolic pressure as the years go by is a biomarker of youth. So aim for under 120/80. Forever.

There is, however, a measurement problem. We all get our blood pressure checked when we go to the doctor’s office. It doesn’t matter why we’re there, that’s the first thing that’s done. But that reading may be falsely high. We’re generally not thrilled to be at the doctor’s office. We’re worried or concerned, which means we’re stressed. And we probably cooled our heels in the waiting room for a while. Also a stressor. And we’re wondering just how much the insurance will pay.

Here’s what I do to try to get a good reading: I ask the nurse to give me a moment before wrapping the cuff around my arm. I sit up straight with my feet firmly planted on the floor and take several big, deep breaths. I relax my shoulders, place the palms of my hands on my thighs and close my eyes. Just for maybe 15 seconds. I’ve tested this more than a few times, first getting the immediate measurement, then mindfully relaxing. It’s pretty astonishing. Try it.

You can’t use blood pressure as a biomarker if the number you’re getting is physician-assisted high blood pressure.

February 26, 2014 No Comments

How old are you, really?

When you tell someone how old you are, are you counting from the year of your birth?

When you tell someone how old you are, are you counting from the year of your birth?

Then you’re lying about your age!

As I’ve mentioned in a previous post, in just about every interview I’ve given and, of course, in my book, Counterclockwise: Your birth date is not your age. Or, rather, your birth date is merely your chronological age, which, after 40, is an increasingly useless, misleading and more often than not downright erroneous number. Your true age, the age that will affect your health, energy, vitality, longevity – you name it — is your biological age, the age of your body.

It’s easy to identify (and identify with) chronological age. We celebrate chronological age every year with parties and presents and candles on a cake. Not to mention “you’re over the hill” birthday cards that are supposed to be funny. And aren’t. We group ourselves (or are summarily grouped according to) our chronological age. But is chronological age a useful, truthful way of looking at how old we are?

No, according to those who study the aging process. What we want is to determine our biological age. And then, my dear counterclockwise readers, we want to turn back that biological clock.

For this and the next several posts I’m going to explore and explain BIOMARKERS, the quantifiable sign posts of biological age, statistical snapshots based on solid research that can help us figure out how old we are inside. Common biomarkers include resting heart rate, blood pressure, cholesterol level, lean-to-fat ratio, aerobic capacity, strength, flexibility. You get the idea.

Here’s the logic of biomarkers: If population studies show that a particular biomarker tends to go up (say, cholesterol) or down (say, muscle strength) with chronological age, then determining your own biomarker and stacking it up against this research will give us a sense of our true age. So a by-birth-certificate 50 year old with biomarkers consistent with a by-birth-certificate 40 year old is, biologically speaking, closer to being 40 than 50.

Let’s start with one of the easiest biomarkers to determine: resting heart rate. The lower it is (within reason), the fitter you are. (Some medications lower the heart rate. This doesn’t count.) The fitter you are, the younger you are biologically. A slow resting heart rate is usually due to the heart getting bigger and stronger with exercise, and thus more efficient at pumping blood around the body. The more blood pumped with each beat, the fewer beats per minute.

What’s your resting heart rate and what does that number mean? Simple.

Take your pulse first thing in the morning, while lying in bed. I am a fan of the under-the-jaw pulse. I can never seem to find and hold onto my wrist pulse. But whatever works for you is fine. Count the beat for 30 seconds (then double it). It’s a good idea to do this several mornings and take an average. Here is a chart that matches that number with various fitness levels at different chronological ages.. Now you are one step down the path of determining your bio age.

Next week: Blood pressure as a biomarker.

February 19, 2014 No Comments

Older ≠ Foggier

As we age, our memory worsens. Period.

As we age, our memory worsens. Period.

Or does it?

Maybe not. Or at least not in this definitive, over-simplified way. The story about aging and cognitive decline is not, I am delighted to tell you, a sad and simple saga of dotage and decrepitude. It is more nuanced, more interesting – and so much more positive – than we previously believed.

Let’s be clear: What we think we know about aging and memory comes from performance tests conducted in research labs. (Everything else – like your 90-year-old great aunt Bessie’s ability to remember the Latin names for 300 species of plants – is “anecdotal.”) But lately some researchers have been pondering the implications of testing older people’s memories in a culture suffused with the belief that old people have poor memories. They have hypothesized that tests that explicitly feature memory may actually serve to invoke performance deficits in older people.

To explore that idea, a group of researchers compared memory performance in younger and older people under two experimental conditions. In one, the instructions stressed the fact that memory was the focus of the study. The experimenter repeatedly stated that participants were to “remember” as many statements from a list as they could and that “memory” was the key. In the second, instructions were identical except that the experimenter emphasized learning instead of memory. Participants were instructed to “learn” as many statements as they could.

Now GET THIS: Age differences in memory were found when the instructions emphasized memory, but no age differences were observed in the experimental situation that instead emphasized learning.

In a related study, researchers had one group of older people read an article about how older people’s memories were worse than originally thought, and another group read an article about how memory actually improves with age. Then the two groups took identical memory tests. Can you guess which group performed significantly better?

Even more interesting to me is the work of Dr. Linda Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity and one of the heaviest of the heavy hitters in the field of aging. She and her colleagues have been studying why and how people remember, and her findings challenge much of this older = foggier refrain. Dr. Carstensen believes that the emotional content of messages and images greatly affect memory. She also believes that we remember what we are motivated to remember, and that motivations change with age and across stages of life.

“The human brain does not operate like a computer”, she writes. “It does not process all information evenly…. We see (and I would add, we remember) what matters to us.”

And what matters to us at 50 may not be what mattered to us at 20. At least let’s hope not.

January 15, 2014 No Comments