Category — prison

It IS broke. Let’s fix it.

I’ve spent more time inside a prison than most civilians. And I’ve probably spent more time reading about and thinking about incarceration than most people who don’t study or work for the corrections industry.

I know, as much as a civilian can know, what that environment feels like. It is soul-crushing. Much has been written about the damage incarceration inflicts—from teaching helplessness to sparking hostility, from exacerbating mental health issues to eroding the physical and emotional health of the children of the incarcerated. And much has been written about the system’s failure to do what we want it to do: reduce crime.

But until I read this study in Lancet (0ne of the oldest, most prestigious science journals),

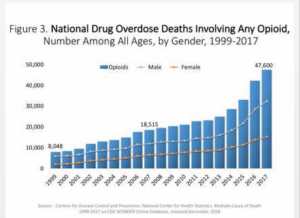

I had not considered that our epidemic of mass incarceration might be linked to the astonishing rise in drug overdose fatalities we’ve all been reading about.

Yes, it’s not news that prison and drugs are linked. The war on drugs accompanied by tough-on-crime mandatory sentencing policies sent and continues to send hundreds of thousands to prison. And yes, a significant percentage of people who commit crimes have some involvement with drugs. (Women’s crimes, in particular, are often to support drug habits.) And yes, drugs are a problem inside prison.

But this study in Lancet suggests an entirely different connection between incarceration and drugs. Based on meticulous crunching of several huge data sets, the study concludes that there is a strong association—a “robust connection”– between the rise in incarceration rates and deaths from drug use.

Data came from 2,600 counties across the country and spanned 1983-2014. The study found that, on average, counties with the highest incarceration rates saw a drug mortality rate 54 percent higher than the rate among counties with the lowest incarceration rates. (The relative poverty of the community accounted for half of this difference; the other half was the rate of incarceration.)

Incarceration, they write, “is directly associated with stigma, discrimination, poor mental health, and chronic economic hardship, all of which are linked to drug use disorders.”

Here’s how one of the co-authors of the study, an economics professor at University of Massachusetts, put it: “In communities with high incarceration rates, it’s making their lives much worse, and making them much more likely to use drugs dangerously.”

In other words, if you came to prison with a drug problem (as a reported 50 percent do), then when you are released (as 95 percent of prisoners are), the conditions are ripe for continued or increased abuse. If you didn’t already have a drug problem, the experience of and stigma attached to incarceration might pave the way to abuse.

July 10, 2019 1 Comment

What does prison accomplish?

Why do we send people to prison?

Well, they did bad things. They should be punished.

An Age of Enlightenment idea, prison was considered a “humane” approach to punishment–far better than cutting off a hand, sticking a hot a poker in the eye, burning at the stake or stoning to death.

But in addition to punishment, incarceration is believed to serve several other purposes. One is incapacitation—preventing crime by removing and restricting the criminal. Another is deterrence—preventing future crime by making the period of incarceration not an experience someone would like to repeat. A third is rehabilitation, the belief that time in prison can be used to help those who’ve committed crimes become the kind of people who will no longer commit crimes.

Arguments can and have been made about the concept of punishment: How much is enough? Should being imprisoned be the punishment or should the daily life of a prisoner inflict punishment? Is being held in isolation cruel and unusual punishment? Death penalty or not?

Arguments can and have been made about rehabilitation: Can people really change? Is providing programming and education in prison being “soft” on crime?

But few have argued against the (presumably self-evident) functions of incapacitation and deterrence. Until now.

A new study (12 years of data from 110,000 convicted felons) conducted by a team of researchers from Berkeley, University of Michigan, SUNY/ Albany, and Colorado, and published in Nature, the pre-eminent science journal, concludes…prepare to gasp:

Prison did not reduce post-release violent crimes.

The study found that sentencing someone to prison had no effect on their chances of being convicted of a violent crime within five years of being released from prison. (The study compared post-release arrests of those who served prison sentences with those put on probation.)

In terms of incapacitation, the study found a preventative short term effect (the time when prisoners were still in prison), but this effect was smaller than assumed. Preventing one person who was previously convicted of a violent crime from committing a new violent crime within five years of their sentence required (statistically speaking) imprisoning 16 such individuals.

The authors bring up related points worth considering:

Imprisonment, because of the culture behind bars, could actually increase a person’s propensity towards violence.

Imprisonment can (has been shown to) exacerbate pre-existing mental health problems or cause new ones that may increase the risk of engaging in violence or being victimized by violence.

Prison life and prison culture can lead to the development or reinforcement of behaviors and attitudes that will make a successful, crime-free life on the outside more difficult. For example: distrust of authority; aggressive coping strategies; lack of self-efficacy and initiative; hypervigilance.

Incarceration, especially long-term incarceration, can erode the familial and social networks that support and encourage a crime-free future.

The authors conclude, from the evidence, that imprisonment does not appear to accomplish what we think it should, what we assumed it did.

What are the choices here? Abolish prisons? Not likely. Ignore the evidence and keep on doing what we are doing? Not smart. Re-think and re-design our current corrections system? Yes.

July 3, 2019 2 Comments

Untold stories

Untold stories. There are so many of them.

I started coming into Oregon State Penitentiary almost four years ago with the idea of starting a writers group for men serving life sentences. Behind bars, encircled by 30-foot high concrete walls, the men who joined the writers’ group (like the other 2.3 million men and women currently in U.S. prisons and jails) were living lives few of us knew anything about. I wanted to give them the tools (but more important, the encouragement, the opportunity) to write about those lives. I wanted them to consider the idea that they were the authors of their lives. That meant, even behind bars, even living these severely constricted lives, they had power over the narrative. They did not have physical freedom. But, at least for two and a half hours twice a month, they had freedom of expression.

I’ve written about the group, what the men taught me about their lives and how it changed me, in A Grip of Time: When prison is your life. The men have developed into powerful storytellers. Four of them have won highly competitive Pen America Prison Writing Contest awards (in 2018 and 2019). Several of them have been published by the Marshall Project. One of them became the first inmate ever to be awarded an Oregon Literary Fellowship.

The writers’ group continues. The stories continue. I wanted to create a public space to share some of the small ones. Most are the products of the 10-minute prompts that begin each writers’ group session. So, after many months of planning, yeoman-like volunteer efforts by artist/designer Liza Burns and man-of-many-parts Brian Burk, I am launching TRUTH TO POWER. The site will feature short essays and even shorter stories written by the men in the writers’ group. I hope their words offer a window–many windows–into this hidden world and the people who live there. Sometimes for their entire lives.

June 26, 2019 No Comments

Talk is cheap. Not.

You’re happy. You’re sad. You’re confused. You’re excited. You need help. Your help is needed. What do you do? You talk to someone. You call someone. You reach out to communicate. Because that’s what we humans do.

But what if you can’t? What if you’re in solitary confinement cut off from human interaction, unable to do this essential thing we humans do?

In A Grip of Time I write about an ingenious, prison communications “system” known as the “toilephone.” Yes, a toilet. Communication between isolation cells involves using toilet plumbing pipes as conduits not for water or waste but for voice. It works like this: A prisoner in isolation flushes the toilet repeatedly until all the water exits the pipes, then sticks his head deep into the toilet bowl, alternately yelling and listening to someone at the other end of the pipe yell back. This is the length to which humans will go to communicate to other humans. That is how important communication is.

Now suppose you are in prison but not in segregation, and you have earned the “privilege” of making a phone call. How does that work?

In state-run prisons, the phone system for inmates is privatized. That is, for-profit companies contract with governmental agencies to provide hardware and software, cloud storage and monitoring. The contracts are based on a commission model, with the provider paying a commission (essentially a kickback) to the governmental agency. These kickbacks, which inflate the costs of the phone calls, are most often paid not by prisoners but by their family members. In Oregon, where I live, phone calls made from a state prison cost $2.40 for 15 minutes, making the state 36 out of 51 for affordability. An Oregon prisoner (inmates are required by state law to be employed) earns between 5 and 47 cents an hour.

I was going to say “you do the math,” but allow me: Using the average wage of 21 cents an hour, a prisoner would have to work more than 10 hours to pay for a 15-minute phone call. If a minimum-wage worker in Oregon used wages earned from 10 hours of work to pay for a 15-minute call, that call would cost $107.50. Oh, and these private phone providers can also extract additional profits by charging consumers (that is, the family members) fees to open, maintain, add funds to or close accounts, or to listen to voice mails.

For those in prison, maintaining ties with friends and loved ones is vital to mental and emotional health, and a key to successful release/ re-entry in the future. (And ongoing conversations with legal counsel can be potentially life-changing.) But we make it expensive and burdensome for that to happen. We make families pay. And we make those in solitary confinement (a practice deemed cruel and unusual punishment by international law) stick their heads down toilets.

June 19, 2019 No Comments

Women who marry men in prison

Women married to men behind bars. What do we know about them?

Almost nothing.

What do we think we know? That they are deranged women attracted to psychopaths. Pitiful, lonely women looking for love in all the wrong places. Damaged women. Control-freak women. Drama-queen women. Women with messiah complexes.

Or, they are saintly, self-sacrificing, celibate women who give it all up to stand by their men.

In other words: We pathologize women who choose to marry men behind bars, and we worship women who have stayed married to their incarcerated husbands.

Like all stereotypes, these “types” reflect bits of truth, much exaggeration, and a lot of ignorance. In fact, the reasons women marry/stay married to men behind bars are as diverse, quirky, open-hearted, misguided, optimistic, rational, irrational, well considered and impulsive as the reasons women marry/ stay married to men in the free world.

In this mostly hidden subculture of women married to men behind bars, there are MBIs (those who were Married Before Incarceration) and MWIs (those who got Married While Incarcerated). What modest attention is paid to these many hundreds of thousands of women is primarily focused on MWIs–and that attention is focused on what’s wrong with these women. How could they? Why would they?

There are those said to suffer from hybristophilia, a mental condition where someone—most always a woman—is obsessively attracted to (gets intense sexual arousal from) a man who’s committed notorious crimes. Yes, it is real thing, documented. The more heinous the crime, the more likely an inmate is to receive “fan mail” (and marriage proposals) from women.

There are women who were victims of abuse and mistreatment by fathers, previous husbands, boyfriends. These women, so the logic goes, figure that if they’re in a relationship with a man in prison, he’s not going to hurt them. He can’t hurt them. Unlike in their past relationships, they are safe.

Or there are MWI women who are calculating manipulators on a power trip. They hold all the cards. The guy is dependent on them for news of the outside, for money contributed to the canteen account, for human kindness—all of which they can dispense, or not, at will.

Or, folks, how about this: Many women who marry incarcerated men fall in love with them. That’s right. Love. Intellectual, emotional, spiritual bonding. The sharing of ideas and stories, beliefs, hopes and dreams. Humor, sadness, random observations. You know…the stuff of life. The sociologist Megan Comfort interviewed dozens of women married or involved with inmates, and she found—contrary to what we think we know–that they were not attracted to the “bad boy,” not attracted to the thrill of risky choices, but rather quite the opposite. The women she interviewed were attracted to what we would consider these men’s “feminine” qualities. The men were thoughtful and communicative. They were listeners. They were interested in establishing and nurturing a lasting emotional relationship (a sexual relationship not being possible, not now and maybe never). They were interested in finding a soul mate not a bedmate. I know two such couples. And I deeply admire their commitment to each other.

These hidden worlds are masked by stereotypes. The more we know, the less likely we are to fool ourselves into thinking we know.

June 12, 2019 18 Comments

To write. To read. In prison.

The white board at last week’s BookExpo convention was a jumble of post-its, each with the scribbled name of a book, each an answer to the question: What book changed your life? I stood there for a long time reading the titles, delighted at the diversity, the scope, the quirkiness. (The Bible, Handmaid’s Tale, Winnie the Poo, To Kill a Mockingbird)

And I thought about the men at Oregon State Penitentiary in the writing group I’ve been running for going on four years. Behind bars, their access to books, books that could change their lives, is extraordinarily limited.

How limited? Have you read the recent coverage of book banning in prison? More than 120 books — ranging from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (okay, I get that) to a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the Attica prison uprisings (and including books on how to make ramen noodles, tattooing, witchcraft) — are on a list of books banned from New Hampshire prisons, according to a prison human rights group.

Outright banning is one way to block access to books in prison. Another is to underfund and undervalue prison libraries. Budgets for buying books can range from nonexistent to skimpy. Yet another is to make it difficult (or impossible) for people to donate books to a prison library.

When I first started coming into OSP to work with Lifers who wanted to write, I had the opportunity to peruse the prison library and saw what was available to them: The shelves were lined with alcohol and drug recovery self-help books, religious tracks, pot-boiler mysteries, Zane Grey-era westerns and not much else.

These men were potential writers of narrative nonfiction. I wanted them to read great narrative nonfiction. I didn’t see any on the shelves. With permission, I started bringing in books from my own home library supplemented by used books from local bookstores.

Three years later, our Lifers Writers “library” (a cabinet made in the prison’s furniture shop) includes work by Alex Kotlowitz and Bryan Stephenson, Joan Didion and Katherine Boo, Anne Lamott, John McPhee, Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, Gay Talese, Jane Kramer, Tom Wicker (yes, the original Attica book), Mary Roach, Tony Horowitz (RIP), James Baldwin, Steve Lopez, William Least Heat Moon—and close to 75 others. They’ve read Evicted, Hillbilly Elegy, The Geography of Bliss, even my coming-of-(middle)-age ballet book, Raising the Barre.

They read. They love to read. Books open the world to them. Reading is helping to make them into the fine writers they are becoming. What book title would they scribble on a post-it? Stay tuned. I’m going to ask them at our next session.

(For me, the book was The Yearling. It was the first book that made me forget who I was and where I was. It transported me. It was the book that made me want to be a writer.)

Why are we reading if not in hope that the writer will magnify and dramatize our days,

will illuminate and inspire us with wisdom, courage,

and the possibility of meaningfulness,

and will press upon our minds the deepest mysteries,

so we may feel again their majesty and power?”

― The Writing Life

June 5, 2019 No Comments

Kids, prisons and acts of kindness

She is standing in line with her son, a harried woman holding tight to the hand of a small child. He is dressed in a little button-down, collared shirt and pants so new they still have the creases in them. Six year olds aren’t known for being quiet and contained. This little guy is. He and his mother are just ahead of me waiting to be processed through the metal detector at Oregon State Penitentiary. I am here for another meeting of my Lifers’ Writers Group. They are here to visit the man who is her husband and his father.

This little boy is one of the 2.7 million children in our country with at least one parent in prison or jail. That’s 1 out of 28. As with many other aspects of the criminal justice system, this heart-stopping statistic has a clear racial component: Almost 60 percent of these children are either black or brown (some estimates are higher). This little boy and his mother are African American.

I don’t know if this is the boy’s first time visiting, but I do know he is scared. That’s why he is so quiet and still. What is he thinking? What is he feeling? Research shows that having a parent in prison can be more traumatic to a kid than even a parent’s death. The effects are measurable: Children of incarcerated parents have higher rates of attention deficits than those with parents missing because of death or divorce, and higher rates of behavioral problems, speech and language delays, and other developmental delays. Some studies suggest these children are at a 6 times higher risk of going to prison themselves.

But right now, he is just a wide-eyed little boy staring at the conveyor belt of the metal detector. He will have to walk through the security door frame and follow a uniformed guard through an iron gate, down a long corridor, through another iron gate, down another corridor to a steel door that the guard will unlock, leading into a big, windowless room where he can visit with his father.

Cory is the guard on duty. I watch as he leans down to talk to the kid. “Wanna see some magic?” Cory asks him. The kid looks up, looks at his mother, then nods cautiously. Cory is a young white guy with an apple-cheeked face. He is my favorite guard.

The mother has taken off her shoes and then kneels down to take off her son’s sneakers. She places them on the conveyor belt. She knows the drill. “Okay,” says Cory, “I’m gonna make your shoes disappear.” He starts the machine, and the shoes vanish. “Don’t worry,” Cory says quickly. “They’re gonna magically come back. Why don’t you go see?” Instructed by his mother, the little boy walks very slowly through the metal doorway.

On the other side, the boy lets out a little yelp. He jumps up and down. He sees his shoes emerge from the conveyor belt. Cory has given the little boy a memory that takes the trauma and strangeness out of this moment.

I take off my shoes, empty my pockets, walk through the security doorway, and wait for my shoes to magically reappear. I smile at Cory. I resist the urge to give him a hug.

(The photo is not of the scene I observed. No cameras are permitted.)

May 29, 2019 2 Comments

On the road

Don was sitting in the audience at the first event, the launch, for my new book, A Grip of Time. He had been released from prison two months earlier after spending 34 years behind bars. One of the original members of the Lifers’ writing group I had started at Oregon State Penitentiary almost four years ago, he was a part of the book I’d be reading from. I’d asked him before the room filled whether it would be okay if I introduced him at the end of the event. He beamed. Don was beaming a lot these days. He was re-learning how to live, and he could barely contain the joy in that.

When I’d finished reading and answering questions, I introduced Don, and the room erupted with sustained applause. I don’t know why people applauded—and possibly they weren’t quite sure either—but I do know, because Don told me, that it was at that precise moment that he felt part of his new community.

***

At Powell’s in Portland I read about Jimmie’s in-prison marriage. Jimmie was another of my Lifers’ group writers. I read about how at OSP you can get married twice a year, either on a Tuesday in April or a Tuesday in October. You can get married between 8 and 10 in the morning. No flowers. No food. You can’t write your own vows. The ceremony takes 3 minutes, and the go-to Reverend charges 20 bucks a pop. I read about how Jimmie was dressed in his best prison blues and had gotten a haircut the day before.

At the end of the event, after I’d read and answered questions and signed books, an older man who’d been waiting to one side came up to me. “I’m the barber,” he said. For a moment I didn’t understand. “I’m the one who cut Jimmie’s hair,” he said. Then we shook hands and he told me that he’d been out 8 years after being down for 28. He was still cutting hair.

***

The first person to raise her hand after one of the Seattle reading events was a well-worn fortyish woman with a smoker’s gravelly voice. She introduced herself by reciting her prison number, then went on to talk about her 19 revolving-door years behind bars, the GED she finally earned, how education was transforming her life. The other day, she told us in her raspy voice, someone from her old life asked her what her prison ID number had been. She quickly recited it. “Huh?” said her former inmate acquaintance. “That’s one digit too long.” That’s when she realized she had recited her University of Washington student ID number instead.

There was not an un-goosebumped arm in the house.

These are the joys of being on the road for this book

May 22, 2019 9 Comments

Stories change lives

“You are a failure, Harvey, you and the whole science of penology…because you rob prisoners of the most important thing in their lives: their individuality.”

That’s Burt Lancaster in his role as Bob Stroud in the 1962 film, Birdman of Alcatraz.

The real Bob Stroud was still alive when the film was released. He died the very next year, his 54th behind bars.

The movie is almost 60 years old. But the dialog could have been written last week. I wish that were a complement for the timelessness of great writing.

It isn’t.

It is an indictment of our penal system, which robs those behind bars of their humanity, their dignity, their individuality.

They deserve it, you say. They did bad things.

Here’s what I would say: Yes, people who do bad things should be punished for their actions. But 95 percent of those we incarcerate get out one day, out into our communities. If prison treats them as sub-human, if prison robs them of dignity, if prison makes them feel less than whole every single day for years, for decades…tell me, what kind of people will they be when they get out?

That’s a rhetorical question. But let me answer it anyway: Angry, distrustful, self-doubting, lacking in empathy, unable/ unwilling to engage in, nurture and sustain authentic relationships. And that’s on a good day. Is it any wonder that within five years of release, more than three-quarters of released prisoners are rearrested.

Bob Stroud, the Birdman (He kept the birds in Leavenworth, not Alcatraz, by the way) transformed himself from killer to not just an international expert on the diseases of canaries but also the kind of man who held wounded birds in the palm of his hand, who fed them with eye droppers…who cared, who found a purpose, who lived a life of meaning. This despite not because of incarceration.

The fact that Hollywood made a movie of his life shows how extraordinary this rehabilitation was. But rehabilitation should be ordinary. It should be the main purpose of prison.

The writing group I started for Lifers at Oregon State Penitentiary is all about encouraging and nurturing individuality through the telling of stories. Telling your story is owning your story. Owning your story is recognizing that you are its author, which means you are also able to craft a new narrative. Stories spark change. Stories change lives.

You can read about those lives in my new book, A Grip of Time.

May 15, 2019 No Comments

Education behind bars

Prison inmates are among the least-educated people in America.

About 40 percent haven’t graduated from high school. (In some states and with certain populations, the number is much, much higher—as high as 80 percent.)

In prison, one of the most effective rehabilitation tools is…that’s right: education. Research, and lots of it, shows that educational opportunities and achievement behind bars keep people from coming back to prison. (95 percent of all prisoners are eventually released. Within 5 years, 75 percent of them are back in jail.) If you release someone with the same skills with which they came in, they’re going to get involved in the same activities as they did before.

It’s not “just” the acquisition of skills that makes learning opportunities in prison a good idea. It is the experience of being in a stimulating environment, of taking part in spirited discussion, of learning to think critically, of reading, of exposure to new ideas. Education does far more than make a person more employable. It makes a person curious, engaged, thoughtful, able to question and analyze. It promotes understanding of the “other.” It allows people to view their lives in context. And, yes, it is statistically proven to prevent recidivism.

So education should be a cornerstone of programming in prison, right?

Of course.

But so very little money is spent on any programming in prison–approximately 6 percent of corrections spending is used to pay for all prison programming—that educational opportunities are sparse. (There are notable, exceptionable programs like Hudson Link, the Education Justice Program, and the Bard Prison Initiative.)

It’s been said that offering classes to inmates is being “soft on crime.” But if getting an education makes it far more likely that a released felon can make a decent, non-criminal life, then offering classes inside is actually being TOUGH on crime. It prevents future crime.

We have an incarceration crisis. We have a re-entry crisis. Everyone, regardless of politics, agrees. In-prison education can help. So can reversing the 1994 ban on allowing inmates to apply for Pell grants that make education affordable to low-income students.

We hear only about the grim life behind bars, the violence, the drugs, the gangs. But there is something else going on. There is a real hunger to learn, to read and talk, to reach beyond the bars and walls, to imagine a new life. I know this first hand. I work with a group of long-incarcerated inmates at a maximum security prison. We read, we write, we talk about the power of stories to change lives. It is not a formal class. But it is education. And I think—actually, I am convinced—it is making a difference.

May 8, 2019 1 Comment