Category — prison

The stories we need to hear

Catherine Jones is smart, articulate, vibrant, passionate—and was the youngest person ever to be tried as an adult for murder. She was 13. Now in her mid-30s, the mother of two beaming, high-energy toddlers, she is the co-director of Outreach and Partnership Development at Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national nonprofit that leads efforts to ban extreme sentences for children.

Arnoldo Ruiz is open-hearted and resolute, a compassionate listener, a tireless advocate for his community, and a devoted father. First arrested at fifteen, he bounced around the youth detention system until, at 18, he began serving a two-decade sentence in a maximum security prison. Today he is the program manager for the Youth Empowerment & Violence Prevention Department at Latino Network, working with at-risk Latinx youth and their families.

Sterling Cunio is a dynamo, as gentle and empathetic as he is powerful and compelling. Incarcerated at sixteen, he spent the next 28 years in prison. He is now an advocate, organizer and storyteller with Church in the Park, a nonprofit that works with the unhoused to restore dignity, relieve hunger, and increase awareness and understanding in the larger community. He also works part-time for the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis and Clark College Law School.

Richard Mireles is dynamic, expressive, optimistic, hard-working—and an ex-felon who spent 21 years behind bars. He is now the director of Outreach and Engagement at CROP (Creating Restorative Opportunities and Programs), a California nonprofit whose mission is to reimagine reentry through a holistic, human-centered approach to advocacy, housing, and the future of work. He is the host of the Prison Post Podcast, which is focused on stories of life after incarceration and what success looks like in reentry.

These are people we need to hear about. These are the stories that need telling. More than 600,000 men and women are released from prison every year. Mostly what we hear about them—when we hear anything at all—is how many quickly return to prison. (Please read my Myth of the Math of Recidivism post.) What we need to hear about is those who make it. Making it is a major accomplishment given the structural and deeply imbedded obstacles they face, the twisted and rocky road from caged to free. These four I write about here are not just making it; they are devoting their working lives, their prodigious energy, their hearts and minds to helping ensure that others have an easier path than they have had.

They know they can never undo the harm they did. But they can try to live a life of meaning and purpose.

Photo: Dusk from my front porch

September 7, 2022 2 Comments

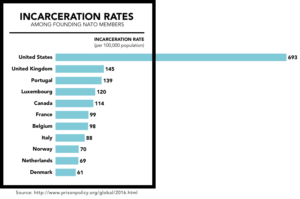

Numbing numbers/ Action items

Not only does the U.S. have the highest incarceration rate in the world; every single U.S. state incarcerates more people per capita than virtually any independent democracy on earth.

One in 7 people in US prisons (203,865) is serving a life sentence. This is more than the entire incarcerated population in 1970.

In California, it costs $106,131 a year to incarcerate an inmate.

New York City spends $556,539 to incarcerate one person for a full year, or $1,525 per day.

K-12 schools spend an average of $13,185 per pupil annually.

It costs the taxpayers of Texas $2.3 million to execute one person.

There are currently 199 people on Death Row in Texas. There are 2,436 people on Death Row in the US.

These are numbing numbers. They can also be action items.

Here is a list of prison reform organizations you can read about, support, and join.

August 31, 2022 2 Comments

Harm and Punishment…and harm

There is a difference between punishing someone for doing harm and harming them in the punishment.

I don’t mean the Hammurabian “eye for an eye” kind of punishment, which obviously inflicts grievous harm—and is meant to. Or any of the punishments humans have invented to kill other humans: burning at the stake, crucifixion, impalement, beheading, drowning, hanging, defenestrating. The list, unfortunately, is much longer than this. And more grisly.

No, I mean the punishment we dole out today to those who do harm. We, the United States, a rational, post-Enlightenment culture with a heritage of social norms, ethical values and empirical beliefs systems. We, the United States, a country believed to be, by more than 50 percent of its citizens, “the greatest country on earth.”

We punish people by removing them from society, from their communities and their families, by taking away their freedom. This is certainly humane compared to slicing off their head or throwing them out a window (that’s what defenestration is). But we don’t just sequester them from society so that they can do no further harm. We put them in cages. We depersonalize them. We take away their ability to make meaningful (or really any) decisions. We create an environment that breeds and reenforces violence and distrust. We create a dangerous, toxic, sealed-off world that, over time, traumatizes. That scars the soul.

The punishment itself, the caging and deprivation, is not designed to rehabilitate. It is designed to inflict harm.

Okay, you say, these people DID harm, Let’s do harm back to them. But here’s the thing: If the punishment creates emotionally and psychologically damaged people who have become accustomed to being treated as sub-human and have come to think of themselves as such, what exactly are we accomplishing? If hyper-alertness, distrust and helplessness become the stuff of everyday life, how is this punishment helping to create people we want to see back in our communities?

Ninety-five percent of those we incarcerate are eventually released. What harm has been done to them during those years—often decades—they spent inside? What if the punishment causes lasting harm, not just for the individual but for all of us?

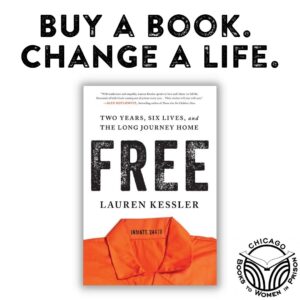

When you read the reentry stories in Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home you will see what it takes to transform the trauma of long-time incarceration into a well-lived life.

August 24, 2022 1 Comment

Costly, ineffective, unfair

“The current system of mass incarceration is costly, ineffective, unfair, racially discriminatory, socially destructive and legally infirm.” That is Robert N. Weiner talking, a Washington, D.C. lawyer and legal strategist, as he introduces the American Bar Association’s 10 Principles on Reducing Mass Incarceration. He is stating facts not opinions..

Costly? Total U.S. government expenses on public prisons and jails: $80.7 billion. On private prisons and jails: $3.9 billion

Ineffective? The U.S. Department of Justice itself states: “sending an individual convicted of a crime to prison isn’t a very effective way to deter crime.”

Unfair and discriminatory? Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at nearly five times the rate of whites, and Latinx people are 1.3 times as likely to be incarcerated than non-Latinx whites.

Socially destructive? As researcher and sociologist Bruce Western writes: “America’s prisons and jails have produced a … group of social outcasts who are joined by the shared experience of incarceration, crime, poverty, racial minority, and low education. As an outcast group, the men and women in our penal institutions have little access to the social mobility available to the mainstream. Social and economic disadvantage, crystallizing in penal confinement, is sustained over the life course and transmitted from one generation to the next. This is a profound institutionalized inequality that has renewed race and class disadvantage.”

Legally infirm? Mr. Weiner is one of the premier legal minds in the country. He ought to know.

At the American Bar Association’s annual meeting in Chicago earlier this month, the House of Delegates passed a resolution to adopt these 10 Principles. These are not radical ideas. They are thoughtfully considered, sensible, humane—and evidence-based. Prison reformers and social justice warriors have been highlighted all these and more for decades. It is notable that the mighty and powerful ABA is now taking this stand.

Limit the use of pretrial detention.

Increase the use of diversion programs and other alternatives to prosecution and incarceration.

Abolish mandatory minimum sentences.

Expand the use of probation, community release and other alternatives to incarceration, and create the fewest restrictions possible while promoting rehabilitation and protecting public safety.

End incarceration for the failure to pay fines or fees without first holding an ability-to-pay hearing and finding that a failure to pay was willful.

Adopt “second look” policies that require regular review and, if appropriate, reduction of lengthy sentences.

Broaden opportunities for incarcerated individuals to reduce their sentences for positive behavior or completing educational, training or rehabilitative programs.

Increase opportunities for incarcerated individuals to obtain compassionate release.

Evaluate the effectiveness of prosecutors based on their impact on public safety and not their number of convictions.

Evaluate the effectiveness of probation and parole officers based on their success in helping probationers and parolees and not their revocation rates.

August 17, 2022 No Comments

When something RIGHT goes WRONG (part 2)

When something is not working, we want to fix it. When something causes harm, we want to stop it. The impulse to make it better is a good one. But sometimes, reforms backfire. Sometimes what we try to fix gets worse in the fixing.

Consider the innovative (and humane) method used to help reduce mass incarceration: electronic monitoring. This is the ankle monitor that tracks (by radio signal or GPS) the whereabouts of its wearer. What a good idea! Instead of putting someone in jail as they await trial, why not control their movements (and insure they will come to court) by attaching an ankle monitor? Instead of caging them for a nonviolent offense, what about an ankle monitor to severely restrict movement up to and including house arrest?

But, here’s the rub (pun sort of intended…yes, jailhouse humor): Localities that use electronic monitoring often contract with for-profit firms for the service. Rather than charge the governments, these companies generally charge the people being supervised. A national survey by NPR found that 49 states — every state except Hawaii, plus the District of Columbia — now allow or require the cost to be passed along to the person ordered to wear one.

A ProPublica story entitled “How Electronic Monitoring Devices Drive Defendants into Debt,” includes the experience of a 19-year-old St. Louis man arrested (his first offense) for driving a stolen car. His public defender managed to get his $1500 bail reduced to $500 (which was covered by the non-profit Bail Project) with the condition that he wear an ankle monitor. For as long as he would wear it, he would be required to pay $10 a day to a private company. Just to get the monitor attached, he would have to pay $300 up front — enough to cover the first 25 days, plus a $50 installation fee. (Fees can range from $150 per month to as high as $1,200. And this does not include the startup fee, which can be up to $200.

In another story, “Ankle Monitoring Practices Are Akin to Extortion,” a 49-year-old longshoreman arrested for a DUI chose 58 days on an ankle monitor rather than a 120-day jail sentence because he was the full-time caretaker for his paralyzed mother. He paid an enrollment fee of $200 plus $13 a day, which totaled more than $1600 for the length of his sentence. He began selling his personal possessions to keep up with the payments.

Others reportedly sell blood plasma to make their payments.

August 10, 2022 2 Comments

When something RIGHT goes WRONG (part 1)

When something is not working, we want to fix it. When something causes harm, we want to stop it. The impulse to make it better is a good one. But sometimes, reforms backfire. Sometimes what we try to fix gets worse in the fixing.

Consider the Ban the Box reform. What a great idea! Get rid of the box at the end of a job application that requires checking if the person had ever been convicted of a felony. This checked box, reformers believed, caused widespread discrimination. Even before the candidate’s qualifications could be evaluated, the checked box gave the potential employer an immediate reason to reject the applicant.

The Ban the Box movement was incredibly successful. Nationwide, thirty-three states and more than one hundred cities banned the box. But, as the painstaking research of Rutgers economist Amanda Agan illustrated, removing this information from job applications did not prevent employers from wanting this information. In the absence of the box, they used another characteristic to discriminate: race.

In an audit study, Agan and a colleague sent 15,000 online job applications for entry-level jobs on behalf of (fictitious) young male applicants both before and after Ban the Box laws went into effect in New Jersey and New York City. On the applications, the researchers randomly varied whether the applicant had a felony conviction and whether the applicant’s name was “distinctly Black or white.” The results were stunning: The gap in employer callbacks between Black and white applicants grew significantly after Ban the Box. With the box, the white advantage for callbacks was seven percent; without it, that advantage leaped to forty-five percent. Without Box evidence, employers “inferred” whether the applicant might have a criminal record. Their inference? Black men were most likely to have convictions. Thus Black men—or rather those with “distinctly Black” names—were disadvantaged. This would include many with no criminal records at all. Their “crime” was being Black.

The employers themselves were not being any more racially biased than the criminal justice system itself, where racial inequality is well documented at every level, from policing to prosecutorial decisions to sentencing. The employers were right. It was more likely for a young Black man to have encounters with the law than for a young white man. Playing it “safe,” in the absence of documentation, they chose not to call back the Black applicants. And so Ban the Box, which had been designed to level the playing field, did the opposite.

I write about the search for employment after incarceration in my book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home.

August 3, 2022 No Comments

How’s THAT working?

Why do we put people in prison?

We are punishing them for doing something bad.

We are making our communities safer.

(Let’s forget the other reason that is sometimes stated—to reform and rehabilitate them—because virtually no one is pretending that this is a priority in the U.S*.)

So: How’s that working?

Well, losing one’s freedom, privacy, home, family, community, access to the natural world, access to information, and ability to have any meaningful control over one’s life is certainly punishment. No doubt about that.

I am writing this not to question whether some individuals deserve or do not deserve such punishment. I am writing this to state the well-researched, evidence-based long-term consequences of such punishment. These include: anxiety, depression, alienation, post-incarceration PTSD, inability to express emotions, difficulty in forming and maintaining healthy relationships, in making everyday decisions, in functioning in routine social situation. (Note I am not mentioning difficulty in finding housing and employment…a given.)

Why should we care? Because 95 percent of all the men and women we incarcerate get out one day, and many of them emerge with these difficulties and deficits. I write about these surprisingly nuanced challenges faced by those reentering after decades behind bars in my book Free: Two years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home.

And now to the other reason: We are safer when we put people in prison for wrongdoing. Are we?

No.

The impact of incarceration on crime is limited and has been diminishing for several years. Increased incarceration has no effect on violent crime and may actually lead to higher crime rates when incarceration is concentrated in certain communities. A study conducted by Berkeley sociologist David J. Harding concluded that sentencing someone to prison had no effect on their chances of being convicted of a violent crime within five years of being released from prison. This means that prison has no preventative effect on violence in the long term.

And then there’s this just-published study by Penn State researcher Andrea Corradi that compared feelings of safety in counties and states across the U.S. Researchers found that people living in areas with high rates of imprisonment were no less afraid of being a victim of a crime than people living in areas with lower rates of imprisonment.

This was true whether the participants lived in a state like Vermont, with a relatively low incarceration rate, or a state like Louisiana, which has the highest incarceration rate in the country. The same patterns emerged among people of different racial and ethnic identities.

So we aren’t actually safer. And we do not feel safer. And many of the 600,000 previously incarcerated men and women who reenter our communities every year have been psychologically and emotionally damaged by their prison experiences in ways that make it difficult for them to become what we want them to be: trusted, productive, engaged members of our communities.

Makes you think, huh?

*In Norway, rehabilitation is at the core of the prison system

July 27, 2022 1 Comment

What do victims want?

In between the violence and the public uproar, in between the reporting and the moving on to the next Thing, in between the crime and the punishment, there is the world of the victims and survivors–the physical, emotional, and psychological space inhabited by those forever changed by the crimes against them, their families, or their communities.

Buffalo, Uvalde, Tulsa. So many victims. And not “just” the ten in the Tops Market but their families and friends, the neighborhood, the community; and not “just” the twenty-two in Uvalde but the 500-plus other students at Robb Elementary, and the families, and the teachers, and the entire close-knit community. The collateral damage. Mass shootings are so common in our country—270 in the first five months of 2022—that most go unnoticed. And the ones that have broken through because they are particularly horrific, like Las Vegas (58 dead), Orlando (49 dead), Sandy Hook (27 dead) Parkland, FL (17) actually result in a small fraction of the many thousands of victims of homicide every year. (The U.S. murder rate is 4.96 per 100,000, which is more than four times the rate in the U.K. and five times the rate in Germany.)

If we hadn’t grown so numb to numbers, these would startle us: One in four people in the U.S. have been the victim of a crime in the past ten years, and roughly half of those were victims of violent crimes. That’s 75 million victims. From 2018-2020, there were 1.36 million reported forcible rapes. The Department of Justice estimates that 80 percent of all rapes go unreported.

And then there are the victims who are neither acknowledged nor given a platform to be heard. They are the hidden victims, the 2.7 million US children who have a parent behind bars. More than 5 million children—7 percent of all US children—have had a parent in prison or jail at some point. (More than 58 percent of women in state and federal prison and nearly 80 percent of women in local jails have children who are minors.)

These children, who have committed no crime, “forfeit…much of what matters to them: their homes, their safety, their public status and private self-image, their primary source of comfort and affection, as Nell Bernstein writes in All Alone in the World.

What I mean to say is that we are a nation populated by victims. .

What do victims and survivors of crimes really want? We are told, we assume, our entire criminal justice system is based on the idea that they want to see the perpetrators behind bars. Maybe forever. That may, indeed, be what some of them want. But is that all they need? Does locking up the person who profoundly altered the course of their life help them process the trauma? Heal? Move forward? Have they ever been asked this question?

June 8, 2022 No Comments

The Revolving Door

Get out of prison. Walk out the gate. Head over to the nearest 7-11. Rob it. Get caught. Go back inside.

Get out of prison. Walk out the gate. Go steal a car. Get caught. Go back inside

Recidivism, the rate at which former inmates run afoul of the law again, is one of the most commonly accepted measures of success (or, actually, failure) in our criminal justice system. The numbers are dismal. About three-quarters of inmates released from state prisons are rearrested within five years of their release.

But wait. Dig a little deeper—as researchers have done—and a far more nuanced picture emerges. For example: Most of the returns to prison in New York — 78 percent — were triggered not by fresh offenses but by parole violations, such as failing drug tests or skipping meetings with parole officers.

This is what the Marshall Project calls the Misleading Math of Recidivism.

When calculating recidivism rates, various states use different measures. Some states lump violating parole (technical violations like missing an appointment with a parole officer, failing to pay a restitution fine, failing to report travel), minor infractions that can trigger arrest (for example, a traffic violation, vagrancy), and committing a new crime as examples of recidivism. Other studies count only convictions for new crimes.

In other words, when we hear about the extraordinarily high rates of recidivism, we often don’t know what’s being counted. What we do know—what many people feel—is afraid. Let those bad folks out, and what do they do? They continue to be a threat to us and our communities. Keep ‘em inside. Throw away the key.

It is infinitely more helpful to think about (and question) those numbers in other ways:

What is being counted?

Why might there be so many parole violations? (Is parole overly punitive? Do parole officers have such excessive caseloads that they have no time to get to know their parolees and help them be successful? What are the most common violations and how can we restructure the demands of parole to mitigate this?)

And, most urgently and importantly, if prison is supposed to be about both punishment and rehabilitation, why is the rehabilitation component so weak (or nonexistent) that for some crimes—burglary and drug crimes top that list–there is, indeed, a revolving door.

Here’s surprising fact to chew on: The most violent prisoners are the least likely to end up back in jail.One percent of released killers ever murder a second time.

I hope you will want to read about the post-prison lives of six people—five of whom committed violent offenses and served decades inside, one with life-long addiction problems—in my new book, Free: Two Years, Six Lives, and the Long Journey Home.

None are back in prison.

June 1, 2022 7 Comments

The rocky road from caged to free

You’re like a ray of sunshine,” the interviewer told her. And she was. Just released after 17 years in prison, almost giddy with optimism and the promise of a new life, Catherine radiated energy and goodwill. She was focused, articulate, and charming. Her smile was infectious. She was confident but not arrogant, poised but not scripted, warm but entirely professional. Her buoyancy, which might have seemed almost adolescent, was tempered by her composure, a skill born of years navigating a life behind bars, of growing up and coming of age behind bars.

She was 30 years old, but for her this was the start of the life she was determined to live. Her résumé included a two-year college degree and a paralegal certification. Inside prison, she had designed and taught workshops for abused women. She wanted to be a teacher or perhaps a nurse. But first she had to establish herself, find a job that tapped into some of her skills and paid her accordingly so she could establish a work history and save for the future she dreamed of.

After the questioning and the conversation, after the smiles and the compliments, Catherine told the interviewer about her homicide conviction, a crime committed when she was just 13. The woman would find out anyway. Catherine thought that if she told the interviewer right then, in person, within the context of the interview that had just taken place, that person would see her in context. If instead her record was later uncovered during the background check almost all employers conducted these days, the interviewer would think she had tried to hide her past. Her crime, a violent crime, would stun them. They would, she figured, just toss her resume in the trash. So she told the interviewer that day. “We’ll call you,” the woman said.

Catherine, that “ray of sunshine,” waited for a call that never came.

How many interviews were just like that one? What job did Catherine finally get? How many years did it take for her to find the work that would change her life—and the lives of so many others?

I hope you’ll want to read her story, and the reentry stories of five others–their long journeys from caged to free–in my new book Free: Two Years, Six Lives and the Long Journey Home.

May 25, 2022 No Comments