Privilege

For a long time, the fact that I was female blinded me to the fact that I was privileged.

At my high school, the boys had a football team, a basketball team, a soccer team, a baseball team, a wrestling team, a lacrosse team, a cross-country team, a tennis team, a bowling team, and a fencing team.

The girls had tennis.

I played tennis.

At the end of each year, the boys had a banquet to honor the athletes. Every boy who played on a varsity team was awarded a big felt letter to be sewn (by a mother) on the back of his letterman jacket. The girls’ tennis team didn’t have banquets or jackets. (In fact, we didn’t have uniforms; we supplied our own tennis balls; our mothers drove us to matches.) At the end of my senior year, I was handed a small envelope in which was a quarter-inch-high black letter L, the first initial of my high school. It was a charm for a charm bracelet. I didn’t own a charm bracelet.

I felt no privilege when I was mugged from behind a half a block from my apartment in Chicago, when I had to run from a group of teenage boys on the streets of Seattle, when men I hardly knew felt they could reach out and touch my pregnant belly, when a man who made “overtures” that I ignored and later became my boss took pleasure out of thwarting my efforts in the workplace.

But then I met B who, at 13, was abandoned by her mother on the streets of Portland and had only her body and her wits to support herself, whose street life led to drugs, whose drug life led to crime, whose criminal life led to prison. And I thought about the privilege of a stable home.

And then I met P, a mother at 15, herself the child of a teen mother, working the only kind of job she’d ever have: minimum wage, no benefits. I met her 14-year-old grandchild who had just dropped out of school and was headed down the same path as her mother and grandmother. And I thought about the privilege of being born into the middle class.

And then I met H, like me a third-generation American, who has been asked, her whole life, “where are you from?” And when she answers “Denver,” they look at her suspiciously and say, “No, I mean, where are you really from?” And I thought about the privilege of having a white face.

And then I met D and learned of an adolescence scarred by bullying and abuse. And thought of the privilege of my hetereosexuality.

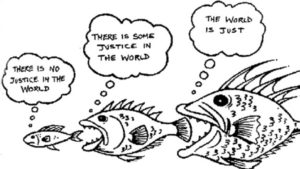

The thing about privilege is that you can be ignorant of it, or you can deny it. You can—as we’re seeing in Trump Era America—embrace it, parade it and employ it as a bludgeon.

You can see it, be an armchair liberal and feel guilty about it.

Or you can use your privilege to help end your privilege.

2 comments

Very challenging. And part of the trap is that there is no “opt out” of privilege. Even if you don’t want it, it is extended to you. And each day we live in that state it tips the scales more. My house increases in value, my IRA accrues interest, the wheels keep on spinning. But preach on sister, beat that drum for all you are worth and maybe “the times they are a changing” will mean something again.

Thanks for that insight about how privilege sustains and enhances itself. It’s like being born with $100 in a savings account. It grows whether you deposit any more, whether you pay attention to, whether you are even interested in it growing.

Leave a Comment